The flower-sniffing bull was the inspiration for a wartime surveillance group in the land down under.

by Rich Watson

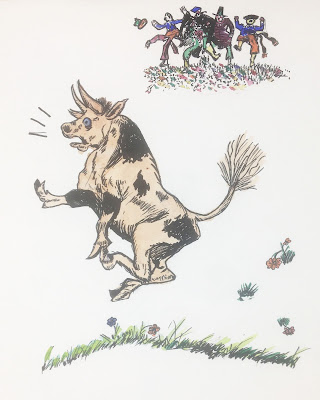

The Story of Ferdinand was a 1936 book by Munro Leaf, with illustrations by Robert Lawson. Life magazine called it “the greatest juvenile classic since Winnie the Pooh.” At one point it outsold Gone With the Wind.

It came out during the Spanish Civil War and on the verge of World War 2. Some interpreted the children’s book within those contexts.

The book’s success, however, inspired Allied forces in Australia in the battle against fascism.

Ferdinand in brief

Leaf, a secondary school teacher turned editor and writer, wrote Ferdinand for his friend Lawson to illustrate. The titular character is a passive bull who’d rather sniff flowers than fight.

By chance, bullfighters mistake him for a tough bull and ship him to Madrid to compete. In the arena, however, his true nature is revealed.

He is sent back home, to his delight.

Ferdinand not only sold well, it inspired an Oscar-winning animated short film from Disney. But it was also misunderstood in places.

Criticism and analysis from the period

In January 1938, The New Yorker said:

Ferdinand has provoked all sorts of adult after-dinner conversations. Some say he’s a rugged individualist, some say he’s a ruthless Fascist who wanted his own way and got it, others say the tale is a satire on sit-down strikes—you see the idea.

Nazi Germany reportedly burned the book. In Spain, it wasn’t published until after Francisco Franco’s death.

Leaf himself told The New York Times:

Letters complained that Ferdinand was Red propaganda, others said it was Communist propaganda, while a number protested it was subversive pacifism. On the other hand, one woman’s club resolved that it was an unworthy satire of the peace movement.

Eventually, the character grew symbolic in other ways, as war grew heavier.

Australia’s coastwatchers and Ferdinand

Australia entered World War 2 in September 1939. They defended the Pacific Ocean beside the British Empire and other countries against Japan and their Axis allies.

The Australian Naval Board consented to a coastwatching network along the Pacific as early as 1922. By WW2, it was in place, under the command of Lt. Cmdr. Eric Feldt.

“Ferdinand” was the code-name under which they operated. Just as the fictional Ferdinand would not fight, so too would these sentries not fight, but gather information on the war in the Pacific.

Feldt recruited from the civilian population in New Guinea, Papua and the Solomon Islands with teleradios, individual radio transmitters and receivers powered by car batteries. Those in strategic areas without teleradios were leant them.

There were over seven hundred coastwatchers. By 1942 they became members of the Royal Australian Naval Volunteer Reserve.

Though the Ferdinand coastwatchers didn’t fight, often they rescued stranded Allied servicemen. One, Lt. Alan Evans, was instrumental in the rescue of future president John F. Kennedy from his naval boat, PT 109.

The Battle of Guadalcanal

In 1942-43, Australia, along with Great Britain and the US, waged the Battle of Guadalcanal in the Pacific against Japan.

Even after the Japanese occupied the Solomons, Ferdinand continued providing intelligence on Japanese installations. As a result, Allied forces fended off air attacks. Among the sentries at the Solomons was a woman, Honorary Third Officer Ruby Boye.

By the fall, Ferdinand informed the Allies of a Japanese counterattack at Guadalcanal in the making. On November 14, the Allies attacked Japanese transports, sinking seven. The remaining four landed at Tassafaronga, but the Allied Air Force attacked their troops.

By February 9, Japan retreated. Later, US Fleet Admiral William Halsey credited the Ferdinand coastwatchers with the Guadalcanal victory.

In 1959, a Coastwatchers Memorial Lighthouse was built in Papua New Guinea.

Munro Leaf later in life

During WW2, Leaf worked for the US Army Department. He and Ted “Dr. Seuss” Geisel collaborated on a pamphlet warning of a malaria-spreading mosquito.

Leaf would write twenty-five books after the war, including two published after his death in 1976.

@byrichwatson

———

Another Behind the Blind coming next, on July 31.

No comments:

Post a Comment